We are often critical in general terms of the way in which Crown agents operate these days.

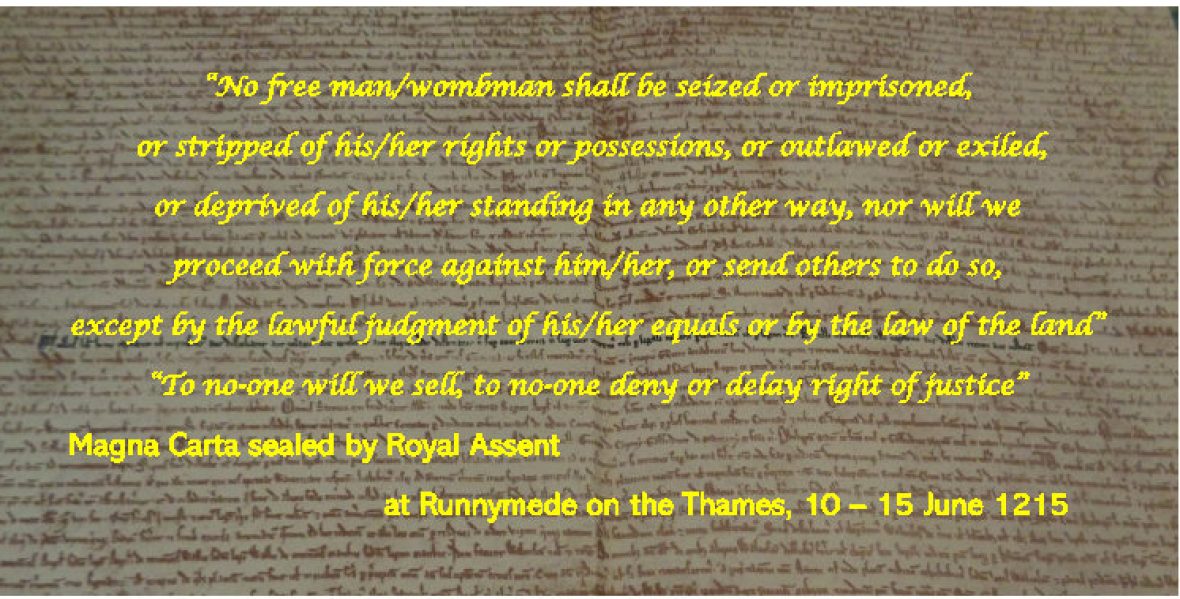

The extract below is taken from the ‘History of Parliament‘ web pages; you may feel that very little has changed in real terms since the 13th Century. Then, as now, the now modern adage – ‘Whatever colour party you may vote for, the government always gets in’ remains pretty close to the mark.

‘All long-lived institutions have their antecedents, and the antecedents of the Lords are to found in the Anglo-Saxon witan which brought the leading men of the realm periodically together with the King for ceremonial, legislative and deliberative purposes. In its earliest history ‘Parliament’, first used as a technical term in 1236, was a gathering of the same type, an assembly of prominent men, summoned at the will of the King once or twice a year, to deal with matters of state and law. So it remained for much of the 13th century. Occasionally, however, these assemblies were afforced by the summons of a wider grouping. At first these extended assemblies – the first known dates from 1212 – served as the means by which the King could communicate with men who, although below the ranks of his leading tenants, were of standing in their localities and well-informed of local grievances. Had the Crown been able to function financially from its lands and feudal revenues alone, these representatives of the localities, the precursors of the Commons, might have remained no more than a source of information for the Crown and a conduit through which it could liaise with its subjects. The decline in the real value of the Crown’s traditional revenues and the financial demands of war, however, transformed these local representatives from an occasional to a defining component of Parliament because the levy of taxation depended on their consent. The theoretical principle of consent had been stated in Magna Carta, but that consent was conceived on the feudal principle that it need come from the King’s leading subjects, his tenants-in-chief, (barons) alone. But as the 13th century progressed this principle gave way to another, namely that consent must also be sought from the lesser tenants as the representatives of their localities. There was both a theoretical and practical reason for this: on the one hand, there was the influence of the Roman law doctrine, ‘what touches all shall be approved by all’, cited in the writs that summoned the 1295 Parliament; and, on the other, there was the practical consideration that the efficient collection of levy on moveable property, the form that tax assumed, depended on some mechanism of local consent. Hence, from the 1260s, no general tax was levied without the consent of the representatives of local communities specifically summoned for the purpose of giving their consent, and only Parliaments in which the Crown sought no grant of taxation met without these representatives. The Crown’s increasing need for money meant it was a short step to the Commons becoming an indispensable part of Parliament. After 1325 no Parliament met without their presence.

‘None the less, although this right of consent gave the Commons their place in Parliament, it did not give them any meaningful part in the formulation of royal policy. In so far as that policy was determined in Parliament, it was determined in a dialogue between the King and the Lords, who came to Parliament not through local election, as was the case with the Commons, but by personal writ of summons from the monarch. Further, the Commons’ right of consent was as much an obligation as it was a privilege. Since subjects had a duty to support the Crown in the defence of the realm, the Commons had few grounds, even had they sought them, on which to deny royal requests for taxation. What did, however, remain to them was some scope for negotiation. To make demands on his subjects’ goods, the Crown had to demonstrate an exceptional need, a need generally arising from the costs of war; and, in making a judgment on the level of taxation warranted by this need, the Commons were drawn into a dialogue with the Crown over matters of royal policy, at least in so far as concerned expenditure. Hence the Crown had to measure its demands to avoid exciting criticism of its government. The consequences of its failure to do so are exemplified most clearly by the ‘Good Parliament’ of 1376, when the Commons, in seeking to legitimize the extreme step of refusing to grant direct taxation, alleged mis-governance, accusing certain courtiers of misappropriating royal revenue.

‘Aside from the granting of taxation, the other principal function of the medieval Parliament was legislative. Even before the early Parliaments lawmaking was theoretically established as consensual between King and subjects, yet, in the reign of Edward I, legislation arose solely out of royal initiative and was drafted by royal counsellors and judges. In the course of the medieval period, however, the assent of Parliament, first of the Lords and then of the Commons, became an indispensable part of the legislative process. Here, however, the question was not, as in the case of taxation, simply one of parliamentary assent, it was also one of initiative. New law came to be initiated not only by the Crown but also by the Commons. In the early 14th century, in what was a natural elaboration of Parliament’s role as the forum for the presentation of petitions of individuals and communities, the Commons began to present petitions in their own name, seeking remedies, not to individual wrongs, but to general administrative, economic and legal problems. The King’s answers to these petitions became the basis of new law. Even so, it should not be concluded from this important procedural change that Crown conceded its legislative freedom. Not only could it deny the Commons’ petitions, but, by the simple means of introducing its own bills among the common petitions, it could steer its own legislative program through the Commons.

‘By the end of the medieval period, Parliament was, in both structure and function, the same assembly that opposed the Stuarts in the seventeenth century. It bargained with the Crown over taxation and formulated local grievances in such a way as to invite legislative remedy, and, on occasion, most notably in 1376, it opposed the royal will. Yet this is not to say that Parliament had yet achieved, or even sought, an independent part in the polity. The power of the Lords resided not in their place in Parliament, but in the landed wealth of the great nobility. For the Commons, a favourable answer to their petitions remained a matter of royal grace, yet they were under an obligation to grant taxation as necessity demanded (a necessity largely interpreted by the Crown); and their right of assent to new law was a theoretical rather than a practical restraint on the King’s freedom of legislative action. Indeed, Parliament amplified rather than curtailed royal power, at least when that power was exercised competently. Not only were the Crown’s financial resources expanded by the system of parliamentary taxation, so too was its legislative force and reach extended by the Commons’ endorsement of the initiatives of a strong monarch, a fact strikingly demonstrated by the legislative break with Rome during the Reformation of Parliament 1529-1536.’